Classical Cadavers: the Intersection of 18th-Century Art and Science

La Venerina by Clemente Susini, Wax sculpture, 1782

Content Warning:

This post contains graphic and potentially disturbing images and descriptions related to anatomical art from the 18th century. Specific triggers include:

Detailed depictions of human anatomy, including dissected bodies and organs.

Illustrations of fetuses and pregnant bodies, showcasing various stages of fetal development.

Vivid and lifelike representations of muscles, bones, and internal organs.

Reader discretion is advised. If you are sensitive to graphic medical imagery or depictions of the human body, you might want to skip this post!

Europe's century-long Age of Enlightenment was marked by a shift towards reason, the questioning of traditional authority, and a reawakening of scientific inquiry. Several fields of study saw great strides in their advancement during this time, including Astronomy, Geology, Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. I'd like to focus on that latter-most concentration-- Biology, the study of life and living organisms.

Although one might expect these 'hard sciences' to develop independently of the arts, there was actually a sort of reciprocal progress between the two. Scientific discoveries in biology and anatomy inspired detailed and accurate anatomical illustrations-- these artistic depictions, in turn, facilitated scientific progress by providing visual aids that were more accessible and understandable to the average person.

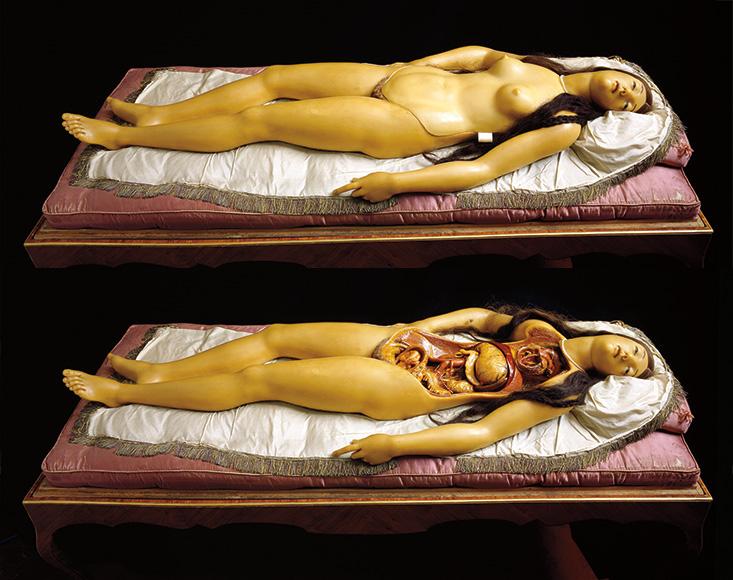

For example, the header for this post is a photo of one of many (more than 2,500!) wax statues created by ceroplastician Clemente Susini and his director Felice Fontana between 1771 and 1893. They were made using the close reference of dissected bodies, with the intention of being reusable, non-perishable educational tools that fellow artists, anatomists, and medical students could use without reliance on real cadavers.

La Venerina by Clemente Susini, Wax sculpture, 1782

Beautiful, life-like women lay in a state of "ambiguous ecstasy" (Shank, 2018) with removable panels on their torsos, thighs, or other portions of the body to depict varying states of dissection with medical accuracy. Despite their slight classical stylization in the face that may result in an eerie appearance to modern audiences, I think these models affect a sense of serenity, and can't help but marvel at the attention to detail in their creation.

Other studies of the body were less-easily palatable.

Selection from The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures by William Hunter, Chalk Drawing, 1774

William Hunter's The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) is an influential work in obstetrics and anatomy, featuring detailed and realistic illustrations of the pregnant human body and fetus in utero. His illustrations provided unprecedented insights into pregnancy and fetal development, significantly advancing medical knowledge. Similarly to Susini's work, the integration of art and science helped disseminate accurate anatomical information to the masses, ultimately making it a landmark in medical literature.

Selection from The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures by William Hunter, Chalk Drawing, 1774

Physicians and anatomists were impressed by the realistic illustrations, but the work did face ethical scrutiny due to the methods used to obtain bodies for dissection-- including accusations of acquiring corpses from executed criminals and pregnant women. Even now, it can be difficult to stomach. I'm endlessly fascinated by the inner workings of the body, but the level of realism on display makes these pieces hard to look at-- it hardly feels any different from studying an actual dissected body. As an artist, though, I'm impressed and inspired by Hunter's rendering and attention to detail; thousands of marks had to be made for the smooth hatching used in his shading, no doubt hundreds of hours of meticulous study.

![GAUTIER D'AGOTY, Jacques-Fabien (1716-1785), Myologie complette en couleur et grandeur naturelle, composée de l'essai et de la suite de l'essai d'anatomie... Paris : chez Gautier, Quillau et Lamesle, 1746 [1748]. | Christie's](https://www.christies.com/img/LotImages/2024/PAR/2024_PAR_23003_0017_004(gautier_dagoty_jacques-fabien_myologie_complette_en_couleur_et_grandeu014541).jpg?mode=max)

Muscles of the hand and arm: six écorchés Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty, Color Mezzotint, 1745/1746

A final influential artist that I wanted to ensure was highlighted here is Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty, a printmaker known for his vivid and colorful anatomical illustrations. His work is more typical of what modern audiences would expect of medical illustrations at the time: slightly-stylized arrangements of labeled body parts, disembodied and inoffensive.

L'Ange anatomique by Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty, Color Mezzotint, 1746

Collaborating with surgeon Guichard Joseph Duverney, d'Agoty's illustrations were noted for their artistic style, which helped to popularize anatomical studies and provided valuable visual aids for medical education. His contributions significantly advanced the field of anatomical art, blending scientific accuracy with artistic expression. I enjoy d'Agoty's relatively simple art style compared to work like William Hunter, as well as the effort he put into composition-- each piece feels like a standalone illustration instead of strictly an anatomical study.

The lasting impact of the Enlightenment on both science and art is evident in today's continued emphasis on empirical observation and precise representation in realistic works! Anatomical illustrations also remain vital in medical education, and the principles established during this era continue to influence contemporary scientific and artistic practices alike.

“The Age of Enlightenment.” Edited by Emilie Gehl Skulberg, The Age of Enlightenment – Niels Bohr Institute - University of Copenhagen, Niels Bohr Institute, 28 Mar. 2014, nbi.ku.dk/english/www/science_in_art/chapters/enlightenment/.

Dunyach, Jean-François. “Europe of Knowledge (Seventeenth–Eighteenth Century).” Translated by Arby Gharibian, Encyclopédie d’histoire Numérique de l’Europe, Digital Encyclopedia of European History, 22 June 2020, ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/european-humanism/europe-knowledge/europe-knowledge-seventeenth%E2%80%93eighteenth-century#:~:text=In%20Europe%2C%20the%20seventeenth%20and%20eighteenth%20centuries,just%20states%20and%20learned%20circles%2C%20but%20also.

“Enlightenment.” Enlightenment | British Museum, The Trustees of the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/collection/galleries/enlightenment. Accessed 18 Mar. 2025.

Lowengard, Sarah. “The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe.” The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe: Jacques-Fabien Gautier, or Gautier d’Agoty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2006, www.gutenberg-e.org/lowengard/C_Chap12.html.

“Muscles of the Hand and Arm: Six Écorchés. Colour Mezzotint by J.F. Gautier d’Agoty after Himself, 1745/1746.” Wellcome Collection, wellcomecollection.org/works/bhettjsb. Accessed 18 Mar. 2025.

Røstvik, Camilla. “William Hunter’s the Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures.” Thinking 3D, 20 Nov. 2017, www.thinking3d.ac.uk/Hunter1774/.

Shank, Ian. “The Anatomical Venus’s Romantic, Macabre History | Artsy.” The Romantic, Macabre History of the Anatomical Venus, Artsy.net, 29 Jan. 2018, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-romantic-macabre-history-anatomical-venus.

Voon, Claire. “The History of Life-Sized, Fully Dissectible ‘Anatomical Venuses.’” Hyperallergic, 15 July 2016, hyperallergic.com/296700/the-history-of-life-sized-fully-dissectible-anatomical-venuses/.

Hey Rei!

ReplyDeleteI can see how studying anatomical artwork from the Enlightenment era can provide a fascinating experience that stimulates curiosity. What stands out to me most about these works is their fantastic combination of the intricate details. Susini created lifelike wax models that matched Hunter’s detailed illustrations perfectly because both combined scientific precision and artistic skill. The detailed realism of these images might create discomfort because they depict graphic content that some viewers find unsettling. This artwork demonstrates a powerful connection to the central theme of scientific progress. Your analysis clarified that these works served as vital instruments for medical advancement beyond their artistic value. Medical illustrations from this time show a two-way relationship between art and science because they both captured scientific findings and helped educate medical experts and the public. Examining the differences between historical anatomical illustrations and contemporary medical imaging methods is important. Contemporary medicine uses MRI and 3D modeling technologies to make anatomical structures easier to study. No modern visualization technique can equal historical anatomical illustrations that combine scientific precision with a compelling visual narrative. Your post successfully reveals a neglected part of art history by clearly and engagingly linking scientific development with artistic expression. Thanks for sharing such an insightful analysis!

Your blog post represents the relationship between art and science in the anatomical illustrated advancements of knowledge. The wax anatomical models by Clemente Susini are an example of how medial art served both an educational and aesthetic purpose. The level of detail that went into the works reflects a great shift toward great observation and precision. I also found it interesting the connection of hunter's anatomical studies to the ethical challenges surrounding cadaver use. There was so much ethical debate, even in present time, in medical research as the use of platinated bodies in exhibits like Body Works. While the exhibits are educational, they also raise questions about consent and the treatment of human remains to be viewed as they are presented and there is so much controversies surround his time. I personally working in the medical field found the prints used to definitely be very educational especially for back then, but I know a lot of things were not done ethically during those times as well, i hope they learned a lot through the explorations and not just for the art pieces and discarded them like nothing.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all, Classical Cadavers is such a clever name for this title. Major props for coming up with that. Secondly, I like the choice of paintings used to depict artwork from the enlightenment era. The paintings were very realistic and that helped to educate the viewer which really ties into the theme of scientific progress. I also chose this subject for my blog post and while I did some research for my assignment, I must say that I've learned much from yours. The anatomy illustrations look so real, I could almost believe it if someone said they were photos. Keep doing great!

ReplyDelete